We find Johann Sebastian Bach in the year 1720 as Kapellmeister in the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. A musician in early mid-career and much better known as an organist than as a composer, Bach busied himself during his six-year sojourn in Cöthen with writing some of his most important instrumental music (rather than the religious vocal compositions his work demanded in such profusion in other postings), while still performing the customary duties of a musical director in a secular court—playing, rehearsing, performing, and conducting—showing leadership as the head musician of the town. This period he spent in a relatively small town (centuries later to become a part of Communist East Germany, the town today with a population of approximately 30,000, its only claim to fame being it’s “Bach-rabilia”), must have allowed him a good balance of family life and work, and within the latter, the flexibility to write without the regular necessity to write for church services.

We know little of the history of the compositions said to be from this period, such as the solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas as well as the Cello Suites. We can well assume that they were first performed in Cöthen, most likely at court, by one of the court musicians. It is also possible though, that in the case of the solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas, Bach himself gave their first presentation, even though he may have played these works on a keyboard instead. That he was a good violinist is a known fact and is prominently documented by his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel. However, the richness and the fullness of their harmonies could, for their maximum effect, be much more successfully and easily executed on a keyboard rather than on a violin.

There is absolutely no record of the context in which the solo violin works were written, nor in what order they were composed, and modern thoughts on whether and how they were performed in the Cöthen years are mere speculation. In fact, while we believe them to have been composed in Cöthen, there is some reason to believe that Bach had already prepared these works while still in his previous post, in Weimar, and that 1720 was the year when he brought them together into a standard collection of six works. Unlike the Cello Suites, the manuscript autograph of these pieces, from Bach’s own hand, does exist–beautiful and elegant as well as meticulous–and it reminds this writer of yet another example of divinely inspired art whose glories seemingly transcend the capacities of any mere mortal soul, Caravaggio’s great painting in which the angel is guiding and dictating St. Matthew.

One wonders where Bach’s inspiration came from and how he must have felt after having completed such a brilliant output. These pieces are monumental achievements. They are masterpieces of composition, of course, but beside Bach’s brilliant innovations, they have a remarkable impact on each player and listener. At first hearing, the listener could be completely taken by the timelessness, the apparent contemporaneous feel, of each of these works, and in practicing them, one loses oneself in the passing of time. From a compositional perspective, the mastery of counterpoint and thematic writing has not lost its mystery; the perfection of the compositional techniques employed has superseded the passage of time. From all perspectives, these works are considered to be a pinnacle of compositional achievement. This is music that presents each listener and performer with an intense experience that cannot be replicated; requiring complete abandonment to the music and the workings of a mind so transcendent.

These compositions place huge organizational demands on a player, who is required to execute a multitude of voices, lines, melodies, counterpoint, and within all that convey the music’s character and impressions. At first, Bach’s individual line is simple, but then, when presented in multiple voices, complexities emerge, and it becomes the greatest of challenges to simultaneously render differing lines while retaining their underlying simplicity. A performer is required to carefully consider the organization of the left and right hands, remembering to pristinely present both the interlocking of musical lines as well as their independence from each other. The lines’ simultaneous independence and dependence of and with each other is at the core of these works. As a performer strives to simplify and organize the lines, that player’s ears and fingers are sharpened and trained, in the mental quest to present relationships between notes, lines, voices and sections that can be both coherent and/or in contrast with each other. Given the richness of Bach’s harmony as well as its purity, the greatest intonation accuracy is demanded, and anything less is blatantly distracting. The smoothness of the melodic line requires mastery of right hand technique, and complete control of its execution. This music requires more than just the possession of high-end technical skills; it demands a player’s coordination its many elements simultaneously, while handling them with both flair and seeming ease. And on top of all that, such technical virtuosity must largely be secondary to artistic priorities.

These pieces also present numerous interpretive challenges to a player. The main question is that of style. A Romantic reading of these works once predominated, with rubato, with wide vibrato, and “meaty” chordal executions a major element of many player’s interpretations. Some of the earliest extant recordings of the complete set are performed in this fashion. Since the renewed popularity and influence of Early Music presentation, the trend is perhaps moving in the direction of performances more in keeping with what we understand been the prevailing style during Bach’s lifetime. Some players go so far as to perform on instruments resembling those of the Baroque era, while others use only the Baroque bow while performing on “modern” instruments, or to use gut strings but with a “regular” or “modern” tuning. There are also those who make no visible modifications to their equipment, while still leaning in the direction of sound and interpretation that are closer to period instrument presentations, handling the instrument “as if” playing a period violin. There is no single “right” way to playing this music–conviction is the key. There is also a question of what to prioritize, what elements of this capacious music to bring to the fore (these choices being both technical and artistic, clearly). Because of the music’s many elements, its multiplicity of lines, plus demanding harmony and rhythms, a player must prioritize a particular element at certain times. For each performer, there are many decisions that must be made, both in planning and in “real-time,” during actual performance. These are issues to which do not lend themselves to one teachable “correct” answer or another, but they certainly need to be recognized and learned and internalized by each individual player. In the end, each performer must make well-informed choices. In truth, it seems to this performer that it is most important to honestly place this music in the context of a player’s life.

At the end of the day, these are some of the most beautiful pieces ever written. They are works that must be played with passion and not fear, that can be felt with hopefulness and not disappointment and hatred, and with adoration and respect. They are to be revered and played with a sense of love for their mysteries and glories, and not because a certain correctness is required. This is music that invokes compassion and has the capacity to reach the deepest and the most inner core of the each person’s soul. It is music that responds to each player’s individuality, reflecting that person’s inner life in ways that strikes a chord of recognition with another person, allowing both the player and listener the musical means for heightened self-examination. In this sense, each interpretation, in its elements that extend beyond learned aesthetics and academic presentation, is stemming from life itself, which is to say that every performance of these works will always be different, emphases and colorings and “meanings” constantly changing. This is indeed living music, that walks in concert with life’s movements.

When encountering such life-altering achievement, people often speak of “divine” inspiration, as though the work was a direct product of godly instruction. Still, this is music of human dimension. Bach was given to normal emotions, as we are aware of his frustrations in some career situations, and knowing of his huge family, we may imagine the demands such a home life placed on the man. He wrote the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin in a town of no particularly great claim, and they have been played ever since by very human musicians for “normal” listeners. Yet amidst all this normalcy is the humbling beauty of this music, a gift we gratefully accept.

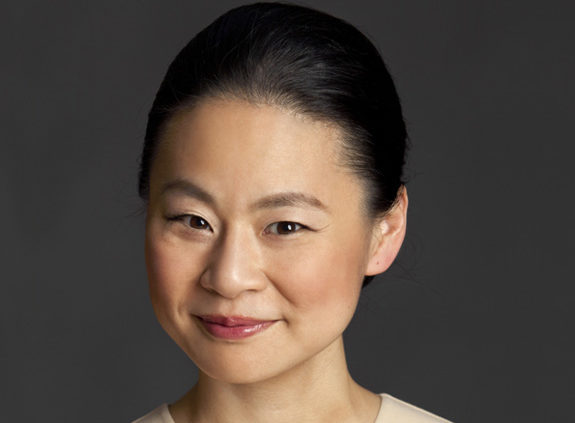

©Midori Goto, 2017